- Screen Colours:

- Normal

- Black & Yellow

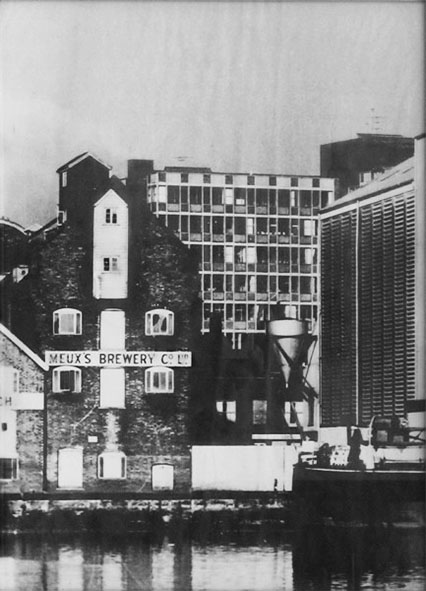

The Friary Meux maltings, Ipswich, in the sixties

This photograph is from The Ipswich Society’s Jepson 1961 Image Archive album (search for ‘Meux Maltings’) and Ron Wragg writes in to confirm that the building was indeed a malting, not a brewery. He knows, because he worked there at that very time. The buildings were between Fore Street and the dockside in Ipswich, near the Customs House, but are now demolished. These are his recollections of the job.

I was living with my parents in Whitton. Friary Meux had two malthouses next to each other on the dock. I knew some people who worked there and they said it was a good job because although it was 7 days a week you only worked half days. In the winter we started early - 6am until 1’ish, and made the actual malt. I wasn’t keen on those early starts because I was courting and wanted to be out quite late in the evening. You can only make malt in the winter, because it gets too hot, too fast, in the summer. In summer you didn’t start til 7am and we did things like unloading the coal wagons - the kells (= kilns) were fed by coal. It was in big lumps and arrived a couple of times a season. You had to climb into the railway wagons and shovel it into wheelbarrows and then into the two coal holes – one for each of the two kells. In the summer we also bagged up the previous season’s finished malt for the Friary Meux brewery in London, and also took in the bulk loads of the new season’s dried barley which we loaded into hoppers.

Malt has to be turned manually and kept aerated to keep cool or it runs away. It was hard to keep all the malt at the same stage together and tidy – the Brewery would check it. You start off by dropping the dry barley from a hopper down into the ‘steep’ which was a brick built pond about four feet deep, and you would add the water and leave it there for 2 or 3 days to soak. Then it was drained off and we jumped over the wall into the barley and shovelled it out with aluminium shovels into pan carts which were a sort of high bin sitting on an axle with big rubber-tyred wooden wheels, one each side of the pan. There is one in the Museum of Food in Stowmarket, and a video of it in use, and two of them are displayed at Snape Maltings. The pan swung so that you could push it and empty it out onto the floor where the malt was made. A load of barley was called a piece, and would be spread out on the malting floor, about 20-30 feet wide and 50 feet long. You would make the piece 12 to 15 inches deep and 6 by 20 feet. Then after 6 or 7 days it grows legs – that is the growing roots. We had to keep turning it with 15 inch wooden turning spades to spread it further and to a uniform thickness. Then when it started you ploughed it with 15 inch wide, two-handled rake with wide triangular flukes, to disturb it and cool it (see the drawing). Once it grew legs you used a malting fork with 4 or 5 wooden tines about 1 inch thick. The maltster - who we referred to as ‘The Doctor’ just because he had been on a first aid course - would grab a handful and say how far ahead we were to extend it today, to cool it the right amount. It mustn’t be allowed to grow shoots or it was ruined – lost all the sugar. As you pushed one piece forward you started another piece behind it, a standard amount set by the team leader.

When it arrived at the far end of the floor there was a loading mechanism which took it 2 or 3 floors up to the kell where it was roasted. The kells were either a 12 foot to 15 foot square of perforated glazed tiles or a steel mesh floor – mostly they were the mesh kind. Heat came up a big flue from the furnace on the ground floor. The firing burned the roots off and they fell down and got bagged up – I do not know what they were used for. It was very dusty. The grain was now malted barley and we shovelled it down a hole in the floor to the bins which were a sort of room, a hopper really. The malt cooled and you bagged it into ‘coomb sacks’ to be weighed and collected by a cycle of articulated lorries which would come up from the London brewery, each bringing us 4 barrels of beer which lasted us until the next lorry load. It was thirsty work – we drank loads. There were no toilets so I will not tell you what we did about that.

There was a manager plus two teams of 4 or 5 of us labourers with a team leader per team – a sort of foreman who said when it was time to go up to the kells and fire it off when it was ready to take it off the steep. There was rivalry between the two malthouses and our Maltster in No. 2 house had a temper and was likely to hit you. No. 1 house was all tall men, but in our house we were all short – which was good as the ceilings were low.

It was hot in the bins: 70-80 degrees. And no vents, just the hole in the middle of the floor. We had to work fast shovelling it into the hopper as the blokes below would be shouting to hurry up so they could bag it, weigh it and get it onto the next lorry. Wading around in the hot malt did slow you down. We wore malting boots made of canvas with a soft sole (maybe rope?) so that when you trod on the grain you didn’t crush it. There were no special clothes – they were always sweaty and dirty – but in the kells we wore paper masks and an extra shirt like a smock because of the dust, and a light cotton cap. We didn’t have goggles though. We were given lapel badges – if you had two you could use them as cufflinks.

The malt had mice in it. And maggots. They were pink and you found them on the boards at the entrance to the bins. You would brush them off before you climbed in. It was very dark – just little side windows with shutters which were usually closed unless you needed to cool the piece.

In the summer we had lunch-breaks in a separate cabin with benches. In the winter we had a one hour break at 7am for breakfast, which was a cheese sandwich – then worked through until 12.30 or 2pm. The whole Maltings shut down for two weeks paid holiday in the summer. Then the new barley would come in, and so would the coal.

We were paid weekly, in cash. The Manager brought it to each of us. I was only 23, the babe of our team. The others were in their forties and would have already worked for 20 years. I only stayed 18 months because I hated the early starts. I think the whole place closed down not long after I left. I am now 83, so I am probably the last one alive to remember the work.

Ron Wragg