- Screen Colours:

- Normal

- Black & Yellow

On a dull Sunday in March, and with the continuing impending onslaught of the coronavirus, some interesting distraction was necessary.

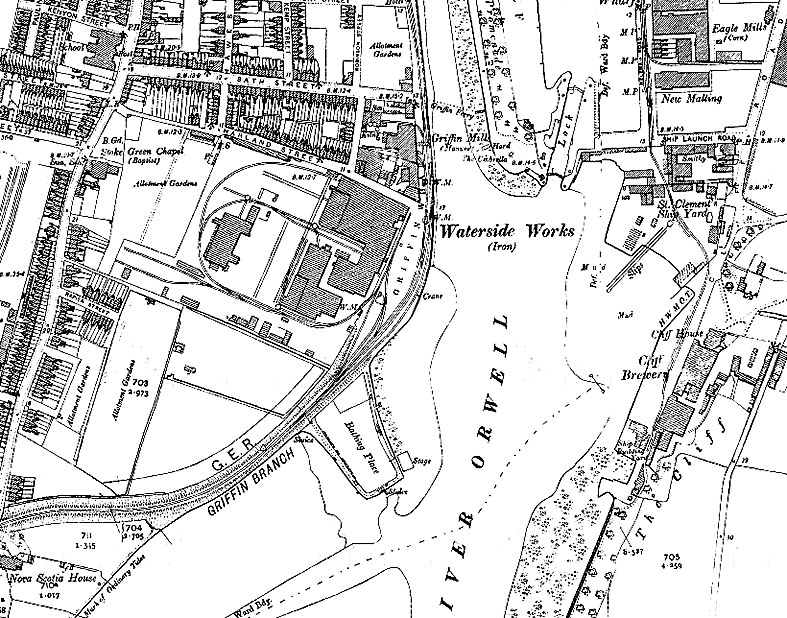

I was pleased therefore to be able to attend the Ransomes & Rapier reunion at Kesgrave Social Club, a venue I had visited to see soul singer Geno Washington many years earlier*. My late father had been an inspector in the machine shop at the Waterside Works in Ipswich for many years.

A proud R & R man through and through, he would have been delighted to see what is being done to keep alive the legacy of this once great world-wide engineering company. From the first railway in China, to revolving stages for the Palladium theatre in London and the Post Office (later BT) Tower restaurant, and to the giant Walking Dragline machines used for open-cast mining, the inventiveness and ingenuity of the R & R engineers knew no bounds. After business collaborations and mergers, becoming part of the Newton Chambers Group, over a century of engineering excellence evaporated when the eventually disgraced ‘businessman’ Robert Maxwell visited the works by helicopter in the mid-1980s and closed it down. The manufacturing heartbeat of the Stoke area of Ipswich was irretrievably lost.

Travelling down to work on a training contract in Kent in the late 1990s, my route often took me down the M20 adjacent to the route being carved out of the Kentish Weald for the Channel Tunnel Railway. All along the route were excavators used in the route construction which were manufactured by Ransomes and Rapier.

It was good to talk to many older former employees, who had an interesting fund of stories about life at the works, including the open days I had attended as a child where I can recall placing a penny on a giant press which promptly flattened it and increased its size tenfold. I also recall seeing Rapier sluice gates on fenland watercourses at Spalding when visiting the Flower Parade over several years, and also seeing a Rapier engine turntable at Didcot Railway Centre in Oxfordshire.

It was good to talk to many older former employees, who had an interesting fund of stories about life at the works, including the open days I had attended as a child where I can recall placing a penny on a giant press which promptly flattened it and increased its size tenfold. I also recall seeing Rapier sluice gates on fenland watercourses at Spalding when visiting the Flower Parade over several years, and also seeing a Rapier engine turntable at Didcot Railway Centre in Oxfordshire.

A central part of the activities at the event was a presentation on the ‘walk’ by a dragline machine from Exton near Stamford, to Harringworth near Corby, a distance of some 13 miles. This dragline excavator, christened ‘Sundew’ after the winner of the 1957 Grand National (all draglines were named after winners of major races), and weighing 1675 tons, with a jib taller than Nelsons Column,‘feet’ the height of several humans, with a ‘bucket’ that a double deck bus could fit comfortably into, ‘walked’ the 13 miles backwards at a speed of one tenth of a mile per hour. A gigantic lumbering leviathan, which however was incredibly efficient at excavating iron ore, used in steel-making at home and abroad. The journey was not without incident, particularly as 10 roads, 5 rivers had to be crossed by laying down hardcore to provide a solid surface, 13 power lines had to be repositioned, and a railway crossed. Not unnaturally, the journey took several weeks.

Amongst the memorabilia on display was a cut away diagram of a dragline from a comic, and also a large poster which boldly proclaimed ‘Maker of large cranes and excavators. Ransomes & Rapier Ltd’. A proud company not afraid to trumpet its worth. Sadly, once Corby steelworks closed down and iron ore could be imported cheaply, work came to an end for Sundew in 1980, with final scrapping in 1987.

A memorable and totally enjoyable afternoon incorporating a real learning experience. Although Ipswich tends to forget and ‘airbrushes out’ its once proud industrial history, the flame of memory still burns bright.

My thanks are due to the organiser Derek Clarke, to the surviving grand-daughter of the late Managing Director, Dick Stokes, and to the wonderful former employees and relatives I met along the way. There is an excellent engineering exhibition at the Ipswich Transport Museum on Ipswich engineering, but it was good to talk to former workers and hear their stories.

An afternoon well spent.

Graham Day