- Screen Colours:

- Normal

- Black & Yellow

Being constantly reminded, with great sadness, of the effects which the present pandemic is having (and will continue to have) on the lives of the young – as well as the old – I thought back to my own childhood.

Like most of my peers, our early life was consumed by six years of World War Two. I have tried to compare my memories of some of the privations suffered by children during those years with those experienced by youngsters during recent months. Most children of my generation were then probably too young at that time to remember an even earlier life of freedom and plenty, so that experiences during the war years for them became the norm.

Above: the Class of 47, Luther Road School, Ipswich

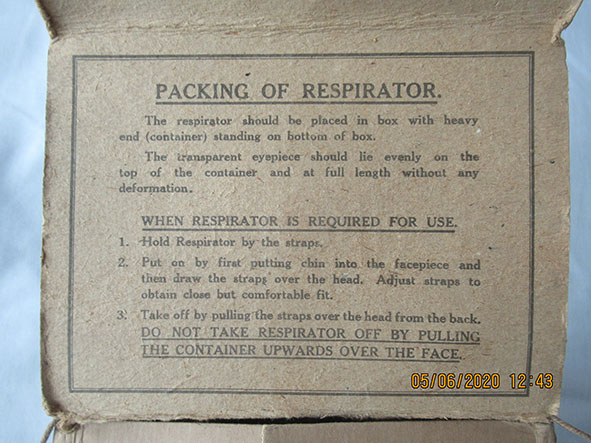

Throughout that time, certainly as children, it was hard for any of us to understand why – just as recently – we weren’t allowed to stray far from our front door. It was early to bed, nights frequently disturbed by air raids (often spent in our garden air-raid shelter, sometimes under our beds), with food rationing and ration books – the imposition of which, of course, went on for long after the war ended. There were no street lights, heavy black-out curtains or shutters at all the windows, all window glass was criss-crossed by sticky brown-paper tape. There were identity cards, air-raid wardens, air-raid shelters, volunteer fire-fighters and fire wardens, and the whole population being fitted out with gas-masks, each one in an individual cardboard box having a string loop to hang around the neck.

Above: Anderson shelter in the garden

There were few open shops with a scarcity of everything. If your garden had iron railings, they were cut down and carted away, purportedly to be used for munitions manufacture. Scrap metal was in great demand.

Above: the author models his wartime gas mask.

Schools were short of all the basics, from books and paper to pens and pencils - with permits for the rest. Education and everything associated with it, including teachers, was in short supply. There were 50 children in every class at our school, with one teacher for each class who covered all subjects except sport and religion. Not only was paper for writing scarce, but what we got was poor quality and had frequently already been used on one side for some other purpose. Pencils had to be shared (one pencil being cut into three), with writing practice done using a slate and chalk. There were scratchy steel-nibbed pens with which we were expected to develop letter-forms and writing styles modelled on those demonstrated by the class teacher. Each position at the two-seater desks had an inset white china inkwell. Every morning an ink monitor went around the desks filling them up and at the end of the afternoon, to prevent loss from evaporation overnight, (even though there was very little heating) the unused remains were carefully emptied back into the bottle. Practice air-raid drills – everyone quietly filing out of class to school shelters – were frequent.

Above: the gas mask box.

At home, we always kept chickens, grown-on from day-old chicks bought at the livestock market. They were kept in our garden beneath fruit trees and fed on scraps. There were hens amongst them who eventually provided us with eggs, and the cockerels were for meat. These were not pets. My father had several allotment plots at the Maidenhall site, where through very hard work and long hours, he grew every sort of vegetable and fruit that a family could want.

All your possessions had to be made to last. New clothes and shoes required coupons, so patch and repair was the norm. Mother darned holes in socks, father re-soled the shoes. Everyone had more than one ration book – some of which had tear-out coupons, others had sections to mark off when they had been used. Most children’s toys were lovingly made by parents – with no plastic. There were virtually no vehicles on the roads. Private motor cars were laid-up as there was no petrol. With very little other traffic, the bicycle was king – but it had to have lights on if ridden at night.

We all now hope that the events which have unfolded since earlier this year do not become the norm. They will surely also be remembered for generations to come?

John Barbrook