- Screen Colours:

- Normal

- Black & Yellow

The opening years of this decade mark 550 years since the birth of the most famous son of Ipswich. Thomas Wolsey (c.1472 to 1530 – his date of birth is uncertain) was the son of an Ipswich butcher* and he was blessed with academic brilliance, rapacious ambition and, until the end of his life, good fortune. His birthplace was probably a house in St Nicholas Street (or St Nicholas Church Lane), long since demolished, at the corner of a passage into the churchyard – although the site of The Black Horse has also been suggested. It’s a matter of opinion which of Wolsey's characteristics was more responsible for his rise to become first minister of Henry VIII, and his chief political confidant, but once he had got to the top, he had a lot to offer.

He was perhaps the finest ministerial mind England ever had until at least the 19th century. He was obsessional in his micro-management of affairs of state and refusal to delegate; his overwork was to take its toll on his health over a long period. In many ways, Wolsey led a charmed life. The young Wolsey benefited greatly from the patronage of the rich and powerful who recognised his gifts and potential. His education was promoted by his uncle, Edmund Daundy, and he secured the scholarship to Ipswich Grammar School, a bequest of Tudor merchant, Richard Felaw. Then, at an unusually early age, he studied theology at Magdalen College, Oxford. As his power increased he collected ecclesiastical titles and properties like stamps and enjoyed the finest luxuries. His greed accounts for his later corpulence and contributed to his poor health.

He was perhaps the finest ministerial mind England ever had until at least the 19th century. He was obsessional in his micro-management of affairs of state and refusal to delegate; his overwork was to take its toll on his health over a long period. In many ways, Wolsey led a charmed life. The young Wolsey benefited greatly from the patronage of the rich and powerful who recognised his gifts and potential. His education was promoted by his uncle, Edmund Daundy, and he secured the scholarship to Ipswich Grammar School, a bequest of Tudor merchant, Richard Felaw. Then, at an unusually early age, he studied theology at Magdalen College, Oxford. As his power increased he collected ecclesiastical titles and properties like stamps and enjoyed the finest luxuries. His greed accounts for his later corpulence and contributed to his poor health.

He went from being a royal chaplain to the Bishop of Lincoln, then became Archbishop of York and finally Lord Chancellor of England. He also became Cardinal Wolsey, Papal Legate whose authority from the Pope in some respects went beyond that of King Henry VIII himself. Wolsey began building Hampton Court Palace in 1514, and carried on making improvements throughout the 1520s. Descriptions record rich tapestry-lined apartments; a visitor had to traverse eight rooms before finding his audience chamber. He always embraced the trappings and rituals which people expected of a man of power, they also satisfied his vanity.

His passion for education influenced his endowments to ‘Cardinal’s College’, today’s Christ Church College in Oxford. He then turned his attention and wealth to the establishment of a college dedicated to St Mary The Virgin in his home town to act as a feeder college to Oxford. He seized the Church of St Peter to be used as the college chapel, which was eventually only returned to the parish through the good offices of Wolsey’s right-hand man and successor, Thomas Cromwell. The College was virtually complete to high standards of building and materials, but within two years was forfeit to the King, as was Hampton Court and all Wolsey’s estate. The only trace we have of the College is the much-eroded Watergate, still to be seen on today’s College Street where the riverbank would have been.

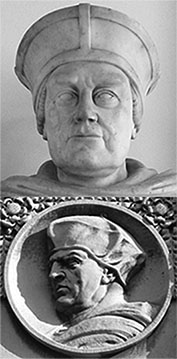

Images: Sampson Strong’s portrait; the drawing attributed to Jacques le Boucq of Artois (1520-1573) in the library of the town of Arras, France; facsimile of the foundation stone of Wolsey’s College held in the Church of St Peter, Ipswich.

Cardinal Wolsey was accused, after his death, of imagining himself the equal of sovereigns; his fall from power was seen as a natural consequence of arrogance and overarching ambition. Much of this can be seen as black propaganda spread by his enemies, now that Wolsey was out of the way of their own ambitions. Yet Wolsey was also a diligent statesman, who worked hard to translate Henry VIII’s own dreams and mercurial ambitions into effective domestic and foreign policy. When he failed to do so, most notably when Henry’s plans to divorce Katherine of Aragon were thwarted by Katherine herself and the Pope, his fall from favour was swift and final. In 1530 Thomas Wolsey died on his way to a possible final and fatal meeting with royal wrath, at Leicester Abbey.

Over the fourteen years of his chancellorship, Cardinal Wolsey had more power than any other Crown servant in English history. As long as he was in the king’s favour, Wolsey had a large amount of freedom within the domestic sphere, and had a hand in nearly every aspect of its ruling. For much of the time, Henry VIII had complete confidence in him and, as Henry's interests inclined more towards foreign policy, he was willing to give his Lord Chancellor free rein in reforming the management of domestic affairs, for which Wolsey had grand plans in the fields of taxation, justice and church reforms.

interests inclined more towards foreign policy, he was willing to give his Lord Chancellor free rein in reforming the management of domestic affairs, for which Wolsey had grand plans in the fields of taxation, justice and church reforms.

Images: Thomas Wolsey by James Williams, Ipswich Town Hall; Tondo of Wolsey, Wolsey Gallery entrance, Christchurch Mansion.

Thomas Wolsey was a unique cocktail of merits and failings – perhaps this lay at the very heart of his extraordinary success. Was he likeable? Would we have admired or feared him? How is he remembered today?

I recently read an excellent biography of the man – and there are a number of such books available – John Matusiak’s Wolsey: the life of King Henry VIII's cardinal (History Press, 2014) which reads like a novel and is most enlightening. Copies are available from Suffolk Libraries. Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, later dramatised for television shows us a Wolsey towards the end of his power (and life). The only known painting of Wolsey by Sampson Strong was made at least sixty years after his death – it may have been a copy of a contemporary portrait. It now hangs in Christ Church College, Oxford. All subsequent images of the cardinal are based on this unflattering profile. We don’t really know what he looked like; and, in fact, he called himself ‘Wulcy’… An enigma.

*Some say ‘a prosperous Ipswich merchant’.

R.G.